Hello from Seoul! 🇰🇷 (And if you’re new here, welcome!)

I know I’ve arrived in the right city because people are drying red peppers on screen doors outside my grandmother’s nursing home:

Before we begin, here’s a poll. Define “family home” as you wish.

I’m just curious to know if anyone else finds it of utmost importance to know what’s available for snacking.

This is the second part of a two-part series on how to rely less on recipes. You can find part 1 here.

In part 1, I introduced my Grand Theory of Cooking™, v0.1, as the following:

Intuition, autonomy, and creativity in cooking = templates + technique

We talked about how templates are simplified recipes that elucidate a dish’s basic structure. But we didn’t discuss how to prepare a template’s individual components. How exactly is a sofrito made? What even is broth?

Enter technique.

I define technique as the understanding of how to prepare and manipulate ingredients to achieve a certain outcome.

Here’s an exercise to start building (or testing!) your technique.1

Look for a recipe. Summarize each step into one word and write it down. Put the recipe away.

Instead of cooking from the original recipe instructions, look only at your list of words and try to think for yourself. How would I make that sauce, based on everything I know about it already? How would I cook those vegetables or that meat?

Make the dish using your existing intuition.

Go back to the original recipe, and see what the author did differently.

You most likely will not get it “right” the first time. But getting it “right” isn’t the point. The point is to get comfortable making your own choices.

But Janey, that’s so vague, and you haven’t taught me anything!

I know 🥲 That’s because, as I’ve learned, “getting better at cooking” is a practice, not a one-time feat. And the only person who can build your intuition is you.

Plus, there are so many techniques out there depending on where you live, what cuisines you tend to cook, and what ingredients you have around you. I couldn’t possibly go into all that because I simply can’t speak authoritatively on, well, any of it. I’ve spent the last 10 years trying to make kimchi, and only recently have I felt closer to the taste I’m looking for.2 I’m still learning, too.

Okay, fine, but how does this exercise work, then? How does it build my intuition?

Through trial and error. Through pushing through mediocrity until your five senses tell you that what you’ve made is good.

Imagine this scenario: one day, after trying various methods of cooking eggplants, you start to ask yourself, why are they always so bitter? And why don’t they crisp up when I bake them?

At which point, you search “why my baked eggplant slices aren’t crispy” on Reddit, and you learn that sprinkling salt on eggplants 15-20 minutes before baking them not only draws out water to maximize crispiness, but also somehow removes bitterness.

Little by little, you build a better understanding of how each ingredient likes to be treated in order to obtain your desired outcome. You start to know when your sofrito is “asking for liquid” (usually wine), as one of my cooking teachers put it, because of the way it crackles and sticks to the pan. You start cooking with your senses. Everything your senses perceive while cooking becomes, over time, intuition.

I like to think of building technique as catching Pokémon.

Each ingredient or technique I master is a Pokémon I catch. Once I catch it, I can consider it part of my collection and deploy it anytime I wish.

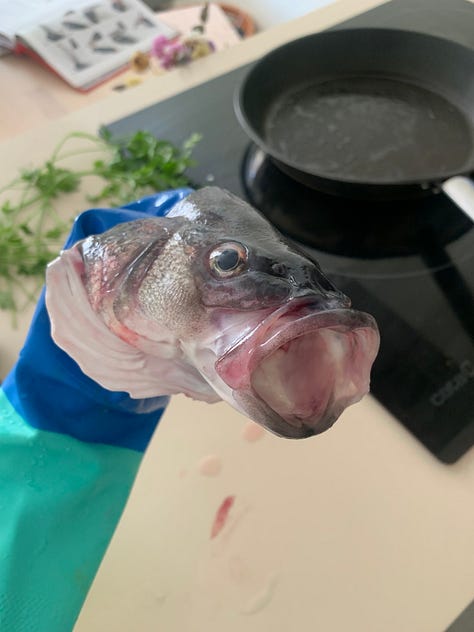

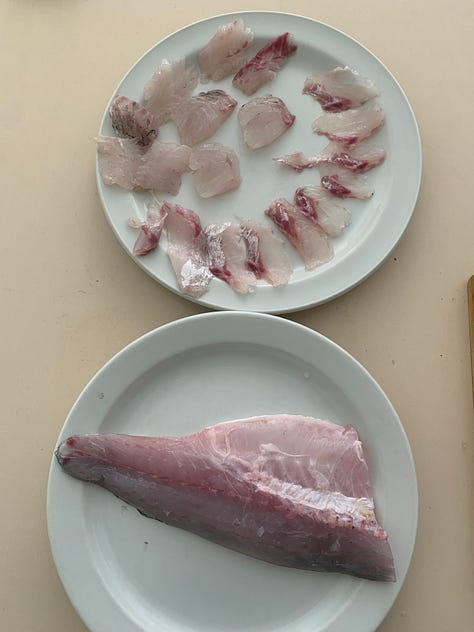

Some Pokémon are easy to catch; they’re just a Youtube video away. Others are more complicated. A whole fresh fish is a more daunting beast than an artichoke, which is more so than a carrot.3 (Though we should not underestimate the potential of a carrot.)

This constant pursuit of new challenges is what turns cooking into an endlessly fascinating game. There’s a unique glory in having the skill, creativity, and power of exceptional Pokémon master home cook. And as long as humanity needs to feed itself, you can rest assured the fun will never end.

Over time, you’ll start making things that are delightful for your palate. And it won’t be because someone told you how to do something, but because you used your intuition and experience to make something uniquely yours. ✨

I love this quote from Several Short Sentences about Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg, one of the best books I read last year:

One purpose of writing, its central purpose - is to offer your testimony

About the character of existence at this moment.

It will be part of your job to say how things are,

To attest to life as it is.

I think cooking by intuition does the same. It offers a momentary testimony of the person in the kitchen. This person marks the “character of existence at this moment” by preparing the last manifestation of the eggplant that started as a bud on a stem, or the fish that led a full life in the sea (hopefully). It’s a moment that passes only once.

And that alone makes it, as all such things are, beautiful.

3️⃣ Barcelona tips for you

Level up your vegetable technique 🥕📈

The book Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables by Joshua McFadden is an excellent place to start, and the Barcelona public library has a copy in Spanish (search Seis Estaciones in the catalog). It’s basically an encyclopedia of vegetables, organized by season, with tips on how to cook with them. Finish the book and you’ll have caught many a Pokémon indeed.

Level up your fish technique 🐟📈

My current go-to source for all things fish is Josh Niland, a chef based in Australia who plays a big role the use-the-whole-fish movement. His book Take One Fish is available in Spanish at the Barcelona public library as Cocina un Pescado. If you continue down the Niland rabbit hole, you’ll end up making ice cream with fish eyes.

Celebrate your leveling up by going out to eat Korean food 🥘

I recently discovered the restaurant Kocina in Eixample. Their menu consists mainly of lesser-known Korean dishes, which I appreciate very much. We tried the squid salad, jjimdak (soy-sauce braised chicken - an excellent dish to test technique on, by the way), and tteokgalbi (beef patties). I thoroughly enjoyed them all.

🌏 Language corner

I love learning onomatopoeia in other languages. Here are a few favorites from my Japanese cooking class:

Kari kari - Crunchy like the chocolate outside a Magnum bar, or bacon.

Saku saku - A dry crunchy, like a potato chip. It should not be used for the crunch in apples or celery, which are moist.

Puchi puchi - The sensation of something such as roe or fruit seeds popping in your mouth.

I personally haven’t cooked in the last week or so because there is too much I needed to try here in Korea, such as this corn ice cream shaped like corn.

But if you’ve tried any new templates or techniques recently, I’d love to know! 👇🏼👇🏼👇🏼

Until August 29,

Janey

I understand that this exercise is harder when it comes to baked goods. I have very little expertise in that world; apologies.

I’m reminded of Ira Glass’s (American radio host) words on taste, though he speaks of it more metaphorically. He says:

Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this…. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.

For some additional inspiration on cooking with new ingredients, here’s a beautiful passage from Maria Nicolau’s Cremo! O Barbarie (see original passage in Catalan here):

The feeling of being alone in front of the fish and abandoned in the face of the questions it raises is an illusion. You are neither alone nor helpless (especially not today, when you all have Google in your pocket), and you are certainly not the first to hold a dogfish or a scorpionfish in your hand, nor to wonder what it is, if it can be eaten, how it is eaten, and where on earth to begin. The history of cooking is the accumulation of answers to the same questions you are asking today, which millions of others have asked before. Go find them.